Understanding the Guyana-Venezuela Border Controversy

The territorial controversy between Guyana and Venezuela is rooted in the European colonization of the Americas. When the controversy arose in the 1800s the United States and Venezuela were allies united against Great Britain. The issue began when Venezuela laid claim to more than 60,000 square miles of territory known as Essequibo, from the then colony of British Guiana. An alliance between the United States and Venezuela against Britain would be unthinkable today. But the conflict is rooted in the intense rivalry which prevailed between Britain and the United States in the 1800s. At that time the confrontation almost led to a war between the US and Britain. In order to understand how matters progressed from that point to the present situation, one has to delve into the conflicts between the great colonial powers beginning over five centuries ago.

Essequibo is integral to the Guyanese nation. The region's captivating forests and waterways are the location and inspiration for most of Guyana's traditional myths, legends and folk songs. Essequibo is, and has always been, populated exclusively by Guyanese. From the inception the area was settled exclusively by the ancestors of the Guyanese of today.

Modern Guyana is made up of three counties- Essequibo along with Demerara and Berbice. These counties were separate colonies that were originally owned by Holland. The Dutch ceded them to Britain all together in 1815. Holland could only have ceded territory that was its own. The British derived their ownership of the three counties of Guyana from the Dutch. Essequibo therefore passed from Dutch to British ownership in 1815. Neither Spain nor its successor, Venezuela, were ever in occupation or possession of Essequibo.

According to historical records the first Europeans to settle Guyana were the Dutch around the early 1600s. First they set up trading posts to barter with the Amerindian tribes in the area. In time they gradually established settlements and cultivated crops. Today there is evidence everywhere of this earlier Dutch presence such as the remains of forts, cemeteries and administrative buildings. There are extensive historical records and physical evidence showing that the British and, briefly, the French had also established settlements in parts of Essequibo during the period when European colonial powers were competing for control of those areas.

It is of particular significance that there is no physical evidence of Spanish settlements anywhere in the Essequibo region today. This is because the Spanish had never established permanent settlements in the area now being claimed by Venezuela.

Upon obtaining independence in 1830, Venezuela sought to define the extent of the territory it had inherited from Spain. The new nation asserted that it owned all the territory going eastward up to the Essequibo River. This area encompasses five-eighths of modern Guyana. Britain rejected Venezuela's assertion and countered that, on the contrary, it was Britain that owned all the territory from the Essequibo River going westward up to the mouth of the Orinoco River.

This standoff led Britain to initiate measures to define the boundaries of its territory. The renowned German explorer and cartographer Robert Schomburgk was commissioned to map out the area. Schomburgk conducted surveys and produced maps in 1841 showing that Britain's territory extended up to the Orinoco. He based these findings on the existence of the Dutch settlements which he witnessed in the area. However, Venezuela rejected Schomburgk's maps on the basis that they had inherited sovereignty over the Essequibo region from Spain. This controversy gained momentum and eventually grew into a serious international episode in the mid-1800s.

In the meantime, the influence and authority of the United States was rising in the Americas. The US had defeated Britain in its war of independence in 1776. The two countries remained enemies and went to war again in the British invasion of Washington, DC, in 1812. Following their defeat in that war, Britain gradually began to recognize the equal status of the US. In 1823 the US proclaimed the Munroe Doctrine under the slogan "America belongs to American People". The US had no more tolerance for European claims to territories in the Americas. The Monroe Doctrine prohibited European powers from asserting claims to any new territories in the western hemisphere. The Doctrine is a cornerstone in the rise of US diplomacy.

On the basis of the Munroe Doctrine the United States gave full support to Venezuela in the disagreement with Britain. Some historians believe that the reason why the US acted in concert with Venezuela was to deprive Britain of control of the strategic and lucrative mouth of the Orinoco River. For its part, Britain consistently maintained that the Schomburgk line defined the perimeter of its territory.

Negotiations between Britain and Venezuela failed to resolve the issue. Venezuela consistently appealed to the US and to the Munroe Doctrine. The US repeatedly expressed its willingness to be a mediator but this was rejected by Britain. This controversy endured from the middle of the 19th century onward. The discovery of gold in the region and increasing competition for control of the mouth of the Orinoco River intensified the dispute and led to a severing of diplomatic relations between Britain and Venezuela in 1887.

The US proposed then that the matter be settled by arbitration but this was rejected by Britain. Eventually, intensive lobbying by Venezuela led to the passage of a resolution by the US Congress in 1895 which It provided that Venezuela and Britain would settle the dispute by arbitration. In December 1895 the US Secretary of State sent a note to Britain in support of Venezuela's position citing the Monroe Doctrine. The President of Venezuela, Joaquín Torres, stated in an address to his Congress that Britain was dangerous to the peace and safety of Venezuela and that Venezuela was within its rights to rely on the Munroe Doctrine for protection.

US President James Cleveland requested and received funds from Congress for a Commission to assist in arriving at a settlement of the boundary.

The terms of reference of the Commission were expressly to "draw a line in consideration of convenience and expediency not to fix the utmost limits claimed by Great Britain as a matter of right." These terms of reference were supported by the Venezuelan government.

In seeking the funding from Congress President Cleveland had asserted that the US had a right to resist British aggression against Venezuelan territory. After the issuance of Cleveland’s message the US mobilized its navy in the Caribbean Sea, Venezuela mobilized its allies in Central America and the clouds of war hovered over the Caribbean.

Treaty of Washington – 1897

Great Britain eventually succumbed to the pressure of the US and agreed to accept arbitration with Venezuela. This decision brought the crisis to an end and led to the signing of a Treaty in 1897 in Washington DC. The Treaty of Washington provided that the dispute would be resolved by an arbitral tribunal at which both Venezuela and Britain would be equally represented. The tribunal's task was to investigate and determine the boundary between British Guiana and Venezuela. The objective of the Treaty of Washington was to lay the basis for a definitive settlement of the territorial controversy. In making its determination the tribunal was required to take into consideration ‘long continued occupation and possession as far as could be established on either side’.

According to article 13 of the Treaty of Washington the parties agreed to accept the result of the arbitration as a "full, final and perfect settlement of all questions referred to the arbitrators". The Treaty was ratified by Venezuela's Congress.

The Members of the Paris Arbitration Tribunal

The Treaty of Washington dictated how the Arbitral Tribunal was to be established. Britain and Venezuela were each to nominate two Arbitrators. Those four Arbitrators would then elect a fifth and final member who would be President of the Tribunal.

Of the two selected by Britain one was Lord Richard Collins, a member of the House of Lords, a Lord of Appeal and Master of the Rolls of the British Judiciary. The other was Lord Rusell of Killowen, a knight who served at various times as a Member of Parliament, Attorney General, Lord of Appeal and Chief Justice.

The first nominee of the President of Venezuela was Melville Weston Fuller. Of the five doctorates in law which had been conferred on him, three came from Northwestern University, Yale and Harvard. He was Chief Justice of the United States and a member of the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague. The second Venezuelan nominee was David Josiah Brewer. He held four doctorates in law including one from Yale. He served as one of the nine Justices of the US Supreme Court and was President of the Universal Congress of Lawyers and Jurists.

These four Judges elected Frederic de Martens, a Russian, as their President. He was such an eminent jurist, a distinguished diplomat and a prolific writer in International Law, that he was the runner up for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1902 and had a postage stamp issued in his honour. His best known book is a landmark text, "The International Law of Civilized Nations". Frederic de Martens presided over the Tribunal. These distinguished gentlemen were later to be accused by Venezuela of gross corruption and skullduggery.

At the hearing itself, Venezuela's legal team was headed by Benjamin Harrison. He was a prominent lawyer, a colonel in the Union army and a Senator prior to being elected as the 23rd President of the United States. The associate lawyers to Benjamin Harrison were Benjamin Tracy, a former Secretary of the Navy and a former US Attorney of New York and James Soley, a former Assistant Secretary of the Navy. The last and most junior member of Venezuela's legal team was Severo Mallet-Prevost, a young Mexican-American lawyer. He went on to play a leading role in the subsequent controversy.

Paris Arbitral Award of 1899

Venezuelans today question why their country appointed American lawyers and judges to represent its interests at such a crucial hearing. The answer is that Venezuela reposed more confidence in those eminent American jurists than in any of its own nationals at the time. Venezuela was free to select any lawyers it wanted to. It chose to hire a powerful American team.

At the hearing President Benjamin Harrison was lauded by the Judges for the force and the eloquence of his arguments. In the final analysis, however, he was unable to convince the panel that Venezuela had succeeded Spain as owner of the Essequibo.

The Tribunal upheld Great Britain’s ownership of most of the territory west of the Essequibo River. But it deprived Britain of its claim to 8,000 square kilometres of strategic territory at the mouth of the Orinoco River.

By the time the Arbitral Tribunal concluded its hearings, its work had taken more than two years. Members of the Panel had conducted an exhaustive analysis of all the available historical records, maps and documents. Oral hearings were then held in Paris before the Tribunal finally issued its decision on October 3, 1899.

In order to implement the ruling by the Tribunal a Mixed Boundary Commission appointed jointly by Venezuela and Great Britain conducted a survey and demarcation exercise between 1901 and 1905. The resulting boundary line was set out on an official map signed by the Boundary Commissioners. Thus ended the differences which had embroiled Venezuela, Britain and the United States for more than half a century.

British Guiana and Venezuela shared a common border with Brazil but that country had not been a party to the Paris Arbitral proceedings. So, the three countries set about to establish their trijunction point. A tripartite boundary commission completed all the necessary measurements and calculations in 1931. The trijunction point was agreed upon by exchange of diplomatic notes in 1932. Thereupon a concrete pyramid marker was erected on the trijunction spot. That spot is located on the top of Mount Roraima, Guyana's highest mountain, where the marker remains to this day. With that, all boundary matters among Brazil, Britain and Venezuela were considered permanently settled. All maps reproduced today reflect these settled boundaries. Except for Venezuela where it is unlawful to publish a map which does not show Essequibo as a "Zone In Reclamation".

Memorandum of Severo Mallet-Provost

However, this was not to be.

In 1944, Severo Mallet Provost, the most junior of the four lawyers on the Venezuelan team at the 1899 hearings, was condecorated with Venezuela's highest national award. Immediately afterward he recklessly produced a memorandum in which he doubted the validity of the 1899 Award. He sealed the memorandum without revealing its contents to anyone. He entrusted it to the custody of an associate, with instructions that it was to be opened only after his death. He stipulated that the contents should be revealed only if his associate thought it fit to do so.

The memorandum was published in 1949. In it, Mallet Provost contended that the 1899 Award was invalid. He alleged that the British Judges and the Russian President of the Tribunal colluded to deprive Venezuela of its right to the Essequibo territory. He argued that in return for Russia's support at the 1899 hearing Britain had pledged certain lands to Russia elsewhere. According to Mallet Provost the American judges were somehow coopted to go along with this scheme. These allegations are devoid of all sense and have long been discredited.

First of all, the parcel of land that Britain has supposedly given to Russia in exchange for the Essequibo has never been located.

Secondly, no convincing explanation has ever been given as to why the eminent American judges would rule against Venezuela for no proper reason when it was Venezuela itself that had nominated them.

Thirdly, neither Benjamin Harrison, Venezuela's lead lawyer at the hearing, nor anyone else involved in the hearing has ever made any mention of this supposed deal in their subsequent writings.

Fourthly, by the time Mallet Provost's memorandum was published all of the other participants in the exercise including all the Judges, all the other lawyers on both sides, and even Mallet Provost himself, were dead and beyond interrogation.

Moreover, long after the publication of Mallet Provost's memorandum in 1949, Venezuela continued to abide by the 1899 award. Only in 1962 did Venezuela inform the United Nations that it considered the 1899 Award to be null and void based upon the memorandum of Mallet Provost. That was the same year as the Cuban Missile Crisis. By then it was the height of the Cold War and British Guiana was agitating for independence from Britain under the Marxist Government of Dr. Cheddi Jagan.

Article 1 of the Geneva Agreement of 1966

Venezuela’s contention that the 1899 Award is null and void sparked another phase of negotiations between the parties. Records were examined once more. Britain, in a spirit of cooperation, intended to afford Venezuela the opportunity of proving its contention before granting the status of independent nationhood to Guyana. Britain had expected that a reexamination of the documents would have put to rest Venezuela's renewed claims. For this reason, Great Britain and British Guiana signed an agreement with Venezuela in Geneva, Switzerland, in February, 1966, which served to reopen the issue.

The colony of British Guiana became the independent nation of Guyana in May, 1966.

Under the Geneva Agreement a Bilateral Commission was appointed to seek “satisfactory solutions for the practical settlement of the controversy between Venezuela and the United Kingdom which has arisen as the result of the Venezuelan contention that the arbitral award of 1899 about the frontier between British Guiana and Venezuela is null and void.” This language is critical to an understanding of the present controversy since these words bear the seeds of important differences between Guyana and Venezuela today.

The sole purpose of the Geneva Agreement is to seek solutions to the controversy which has arisen. We therefore need to be specific about the controversy that is being referred to. On that point the Geneva Agreement is clear. It is the controversy which has arisen over Venezuela's contention that the 1899 Award is null and void. In other words, the only question the parties have agreed to examine is whether Venezuela's contention, that the 1899 Award is null and void, has merit. Furthermore, the purpose of the Geneva Agreement is not to directly resolve this conflict but to identify a mechanism through which the controversy is to be resolved.

Guyana therefore has nothing to prove under the Geneva Agreement. As was agreed in the Treaty of Washington of 1897 Guyana, as the successor state to Great Britain, has accepted the 1899 Award as a "full, final and perfect settlement”. The onus is on Venezuela to establish its contention that the 1899 Award is null and void. The words "practical settlement of the controversy” in Article 1 of the Geneva Agreement refer only to whether or not the Award is null and void. Those words do not refer to where the boundary should be located.

The Geneva Agreement does not signify that Guyana or Britain ever agreed that the boundary between Guyana and Venezuela must be subject to automatic revision. It is by this misinterpretation that Venezuela unilaterally and unjustifiably transforms the agreement into a demand for Guyana's territory.

The Geneva Agreement sets out a range of mechanisms to be utilized to resolve Venezuela's claim. The Agreement first provided for a Mixed Commission. If the Mixed Commission could not produce a result within a given time frame of four years then the UN Secretary General would select another option.

The Mixed Commission failed to come up with a solution. Venezuela never utilized the Commission as a forum to prove its contention that the 1899 Award was null and void null and void but rather sought to use it as a means to obtain a territorial concession from Guyana. The Commission had no such mandate.

Breaches of the Geneva Agreement

According to the Geneva Agreement, upon the termination of the Mixed Commission the two countries would choose another means of settlement. Instead, Venezuela then embarked on a series of hostile and aggressive actions designed to coerce Guyana into giving up its territory. The catalogue of violations of Guyana's sovereignty and territorial integrity is too lengthy to enumerate here. Three of the most egregious instances were:

The Invasion of Ankoko Island: Venezuela invaded Ankoko, an island several square miles in size, half owned each by Venezuela and Guyana, strategically located in the Cuyuni border River in 1968. Since then to the present time Venezuela has placed military personnel in continuous occupation of the entire island in flagrant violation of Guyana’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.

The Rupununi Rebellion: Rupununi is situated in the vast savannah in the southwest region of Guyana. In the 1960s, in the absence of modern infrastructural and communication linkages, certain elements of the population there harboured disloyalty to the central government which is based on the northern coast. Venezuela provided military training and equipment to those individuals. The rebels launched an uprising at the end of 1969, killing several policemen and other officials. They seized control of the region and announced that they had seceded from Guyana. The Venezuelan army was poised to invade and occupy the area. However, before they could mobilize, the Guyana Defence Force was able to quell the rebellion and resume control of the area. The rebel leaders, who were the patriarchs of two influential Guyanese families from the Rupununi, were afforded sanctuary in Venezuela. Today, the rebels and their descendants live comfortably in the Venezuelan city of Puerto Ordaz.

The Hydro Power project: In the 1970s Guyana commenced construction of a facility known as the Upper Mazaruni Hydroelectricity Project. The project would have produced 1200 MW of electricity and powered a smelter that would have produced 200,000 tons of aluminum per year. Venezuela opposed the construction of the facility on the ground that they had a claim to the territory. As a result, the World Bank backed off from financing the project resulting in heavy economic losses for Guyana.

The Protocol of Port-of-Spain, 1970

In the wake of the Rupununi Uprising the Government of Trinidad and Tobago brokered a new agreement between Guyana and Venezuela, the Protocol of Port of Spain. The purpose of the Protocol of Port of Spain was to lessen tensions and allow for a cooling off period. The Protocol of Port-of-Spain imposed a 12 year freeze on any actions or claims by either side. At the expiry of that 12 year period, Venezuela indicated that it would not renew the Protocol.

Upon the expiry of the Protocol of Port of Spain, the parties reverted to the provisions of the Geneva Agreement. A mechanism had to be identified within the Geneva Agreement, other than the failed Mixed Commission, that would allow Venezuela to prove its rejection of the 1899 Award.

Article 4, Para 1 of the Geneva Agreement

Consequently, in 1984 the parties reverted to Article 4 of the Geneva agreement. Article 4 states that if the Mixed Commission fails to resolve the issue the parties can choose one of the means set out in Article 33 of the UN Charter. Article 33 outlines measures to be used according to international law for the pacific settlement of disputes. Under the Geneva Agreement, should none of the measures identified in Article 33 be acceptable, the parties can refer the matter to the UN Secretary General.

The Good Officer Process

It was at this point that the two countries chose to apply the UN Good Officer process. This procedure provides for the UN Secretary-General to appoint a Good Officer and for each country to appoint a Facilitator. These three officials would negotiate, not to resolve the controversy, but to identify a means by which the controversy could be resolved. It is this process that has been in place from 1984 until the present time.

Over the years a number of outstanding Caribbean statesmen have been appointed by the UN Secretary-General to serve as his Good Officer in this process.

From 1984 to now Venezuela has failed to produce any evidence to establish its contention that the 1899 Award is null and void. What it has done within the Good Officer Process is to attempt to obtain territorial concessions from Guyana.

Venezuela is now calling for a new Good Officer to be appointed and for this process to continue. Guyana's position is that the Good Officer process is no longer viable. Guyana is convinced that only a juridical solution could serve to resolve the issue at this time.

Arrested Economic Development

For the duration of the Good Officer process, Venezuela has been relentless in its efforts to thwart Guyana’s economic development. This policy has been implemented through persistent aggression, intimidation and violations of Guyana's sovereignty and territorial integrity.

Of these the four most egregious have been:

Venezuela’s Maritime Claims

- The Maritime Decrees of 2015:

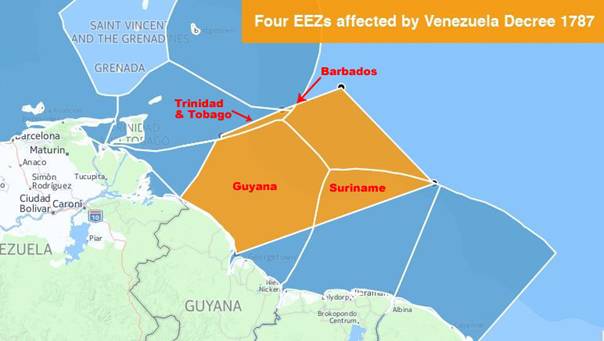

Guyana celebrates its Independence on the 26th of May. Independence Day in 2015 was also the occasion for the swearing in of President, Brigadier David Granger, and his new Government following elections which were held on the 11th of May. On that very day Venezuela promulgated Decree No. 1787, declaring the shaded portion on this map as the area Venezuela now regards as its maritime space. By this decree Venezuela sought by domestic law to annex virtually Guyana's entire Exclusive Economic Zone. The Decree specifies that Venezuela's naval forces should establish and exercise control over a defence zone in the area subject to the Decree.

The promulgation of Decree 1787 was preceded by an announcement one week earlier by the ExxonMobil oil company that they had made a significant oil find 120 miles off the coast of Guyana. As you can see from the map, the area where oil was discovered is not adjacent to Venezuela's land claim but far to the east of it. In order to lay claim to Guyana's oil Venezuela has used the sovereign continental territory of Guyana to generate maritime space for itself.

Such action flies in the face of all norms and conventions that govern the relations between states. Venezuela’s Maritime Decree denies Guyana its legitimate right to pursue its existing development initiatives.

Venezuela’s lines of maritime delimitation violated the territorial integrity of a number of other CARICOM countries also. For this reason, Heads of Government of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) meeting in Barbados in July 2015 called upon Venezuela to withdraw the Decree in so far as it infringes upon the territorial integrity of any CARICOM Member State. Venezuela complied but they immediately promulgated a second decree laying claim to essentially the same area but without issuing any coordinates.

- Mining and Forestry Claims (Aurora)

In 2015, the Venezuelan Ambassador in Ottawa, Canada, wrote to Aurora Ltd, a Canadian mining company, threatening legal action should they continue with their gold mining operations in Essequibo. The company informed Venezuela that their claim was baseless. Venezuela’s actions against Aurora is the most recent example in a pattern of intimidation against companies operating in Essequibo.

- The Teknik Perdana incident:

In 2013 a vessel designed to conduct oil exploration activity was conducting seismic testing in Guyana's maritime zone. The vessel was contracted to Anadarko Corporation, a US company. A Venezuelan gunboat seized the vessel within Guyana's waters and escorted it to Venezuela from where it was eventually released. As a result Anadarko discontinued its petroleum exploration activities in Guyana.

- The Beale Aerospace Project

The Government of Guyana signed an agreement in the year 2000 with Beale Aerospace, a Texan company, to establish a satellite launching facility in Guyana. Venezuela issued threats to both Beale Aerospace and to Guyana with the result that the company abandoned the project.

Article V of the Geneva Agreement – Para 2

The boundary between Guyana and Venezuela has been determined by the 1899 Award which is binding on the two countries. Venezuela's rejection of that arbitration Award cannot confer on Venezuela any rights to Guyana's territory as is often asserted by Venezuela. This is clearly spelled out in Article 5 of the Geneva Agreement.

"No acts or activities taking place while this Agreement is in force shall constitute a basis for asserting, supporting or denying a claim to territorial sovereignty in the territories of Venezuela or British Guiana or create any rights of sovereignty in those territories, except in so far as such acts or activities result from any agreement reached by the Mixed Commission and accepted in writing by the Government of Guyana and the Government of Venezuela. No new claim, or enlargement of an existing claim, to territorial sovereignty in those territories shall be asserted while this Agreement is in force, nor shall any claim whatsoever be asserted otherwise than in the Mixed Commission while that Commission is in being".

Guyana is now firmly convinced that all options under the Good Officer process have been completely exhausted. Venezuela's unprincipled actions to violate Guyana's sovereignty and territorial integrity have occurred even during the Good Officer process. As such, the only option acceptable to Guyana at this time is a juridical solution to resolve the differences.

Guyana has sought to persuade the United Nations Secretary General (UNSG) that, under the Geneva Agreement, he should decide to refer the matter to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) for a juridical solution to the controversy.

Guyana has the support of the Commonwealth for this position. In November, 2015, Commonwealth Heads of Government issued a Communique in which they expressed full support for the UNSG to choose a means of settlement in keeping with the Geneva Agreement. The 53-member organization also maintained their support for Guyana’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.

Guyana has called on the United Nations to refer the matter to the ICJ ever since Venezuela asserted its illegitimate claims to Guyana;s maritime territory in 2015. In December, 2016, the outgoing Secretary General of the UN, Mr. Ban Ki Moon, decided that the Good Officer process would continue for one more year and, if there is still no agreement under that process, the matter would be referred to the ICJ. The current UN Secretary General, Mr. Antonio Guiterres, has endorsed that decision.

Guyana supports this decision by the United Nations.

Recourse to Judicial Settlement

It is worthwhile to reflect on some of the effects of Venezuela’s contentions:

Firstly, even if the 1899 Award is deemed to be null and void, this does not automatically mean that Essequibo belongs to Venezuela. In that case the situation would revert to the pre-1899 position. Guyana will therefore be free to reprise the previous British claim to the mouth of the Orinoco which British Guiana lost in the 1899 Paris Award.

Secondly, if the Award is null and void a new methodology would have to be put in place to determine the boundary. That process must take into account that Guyana has been in sole, continuous and undisturbed possession and occupation of the area up to the present time.

Thirdly, by rejecting the 1899 Award, Venezuela has unilaterally abrogated the tripartite agreement it entered into with Guyana and Brazil in 1932 which fixed the trijunction point. By rejecting the trijunction point, Venezuela will be initiating yet another disagreement. This time it will be about the location of their border with Brazil.

Fourthly, as of 2017, the Guyana-Venezuela boundary has now been settled for 118 years, since 1899. There are numerous boundary controversies and treaty settlements across the globe. Overturning the 1899 Award will create a precedent for challenging long-standing boundary treaties and resurrecting old conflicts. Reopening a large number of boundary disputes would further increase insecurity and instability worldwide.

Finally, in support of his contention that Essequibo belongs to Venezuela, President Nicolás Maduro stated in 2015 that Essequibo was named after a Spanish explorer by the name of Esquivel. There is no definitive theory about the origin of the word Essequibo. However, its origin is irrelevant when one considers that America was named after an Italian explorer, Amerigo Vespucci. Based upon President Maduro's reasoning Italy can lay claim to the United States.

In conclusion, Guyana is committed to a just and lasting solution to the controversy that would lay the basis for continued good relations with Venezuela thereafter. Guyana is committed to an amicable solution within the framework of the Geneva Agreement and in accordance with International Law. All Guyanese strive for peace, friendship and good neighbourly relations with the Government and people of Venezuela. Guyana is grateful for the understanding and support of its friends in the international community.

Prepared by -

The Embassy of Guyana.

Beijing, People's Republic of China.